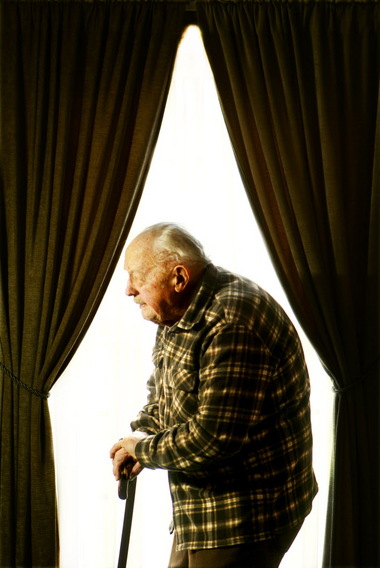

“There are no ordinary lives,” said Ken Burns of those who served in a global cataclysm so momentous that the filmmaker simply entitled his 2007 documentary “The War.”

Many who served in so many different ways during World War II are gone now.

Some took their stories with them.

But not this one.

Eugene Quidort had a guardian angel — a girl, by the sound of her voice.

It was a voice he heard on June 10, 1943, when Quidort was aboard the “Esso Gettysburg,” a tanker hauling 120,000 barrels of crude oil straight into the sights of a German U-boat lurking off the Georgia coast.

Quidort was a cadet-midshipman, partway through his training at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and serving on his first ship.

The West High School graduate (class of '39) had a hankering to go to sea ever since he was a young boy, when a Great Lakes freighter captain who lived on Quidort's street took the youth on a short voyage across Lake Erie.

“This was during the Depression, and when I sat down in that [ship's] fancy dining room and ate like a millionaire, I said, ‘I'm going to be a captain when I grow up,' ” Quidort, 92, of Cleveland, recalled.

During World War II, he joined the more than 200,000 members of the American Merchant Marine who delivered tons of supplies and millions of troops to combat zones around the world.

The thought of sailing on uncertain seas, stalked by German submarines and bombers during the war, initially didn't faze Quidort. “Nervous? No, I was dumb,” he joked.

That changed on that June day in 1943 aboard the Esso Gettysburg.Quidort recalled that he had just had grabbed an engineering book to study and was headed for the engine room when he felt a tap on his shoulder. He turned around, but nobody was there.

Then he heard a girl's voice, clear as the blue sky overhead: “I wouldn't go down there if I were you . . . Go to the flying bridge and get some sun.”

Quidort shrugged, headed to the upper decks of the ship, sat down and opened the book just as two torpedoes slammed into the ship, one directly into the engine room.

“It sounded like a giant sledgehammer — Boom! Boom!” he recalled.

As the ship tilted back on its stern, Quidort ran for bow and jumped. Five minutes later the tanker slipped beneath the waves, taking more than 40 crewmen with it.

Quidort and other survivors swam through oil and water toward an overturned lifeboat. He felt a thump against his leg. Sharks. Quidort said he could only think, “What the hell are we going to do?”

Suddenly a school of dolphins darted between the sailors and the sharks. “They knocked all these sharks out of the way and waited until we got the lifeboat turned over,” Quidort said.

“They stayed with us the whole time,” he added. “Then, when we got everybody in there and settled down, they practically waved goodbye to us.”

Quidort and the 14 other survivors were rescued the next day. He never again heard the voice of the girl he called his guardian angel.

It was a daunting beginning to his service in the war, but Quidort said, “I figured bad start, good ending.”

And that's just how it turned out as Quidort safely sailed on four other vessels — including a tanker, troop transports and a hospital ship — to England, France and Mediterranean ports.

There were always reminders of the risks, including nights when there'd be a sudden flash on the horizon as a fellow convoy vessel was hit, or warships dropped depth charges.

There also were the natural elements to confront as the ships battled heavy seas. Quidort remembered times when he came off watch duty with his face whipped bloody by slashing wind and rain.

Some of the dangers he skirted were ashore, when he visited London while it was still under attack by German bombers and rockets.

Quidort said he was stunned by the devastation in the city. “You don't realize what war is, until you go to a place like that,” he added.

After delivering troops or supplies, the ships would sometimes return to the U.S. with German POWs or wounded GIs.

Quidort remembered one prisoner who was put on a work detail, painting the ship, but kept “losing” his brush over the side. Quidort said that attitude changed when he told the POW that he'd follow the next brush that went into the sea.

He also recalled the wounded U.S. soldier who came aboard still clutching his weapon. Quidort said he was about to take it away when he was warned that the man had 15 members of his unit killed around him, and ever since, “he's still talking to that gun.”

Quidort left the gun alone, after making sure it wasn't loaded.

As the war wore on, Quidort missed his wife, Mary, whom he'd married after his first ship was torpedoed. He didn't see their first son until five months after the child was born.

Quidort said that after a while he stopped worrying about the risks. “What're you going to do? That's life,” he said with a shrug.

But his wife worried, with good cause. More than 8,000 Merchant Marines were killed at sea, and another 12,000 wounded in the war.

Quidort said the best part of his service came “when the war was over and I could come home.”

After the war, he and his wife raised three children while he worked as a tool and die maker until he retired.

Looking back on World War II, Quidort said, “As far as [Adolf] Hitler goes, I did my part.”

With a little help from a guardian angel, of course.

A video link of Eugene's experience can be viewed HERE.